Some Thoughts on the Economics of Ageing, Geriatrics and End-of-Life

Daniel Slottje and Brendan Rogers

Daniel Slottje* and Brendan Rogers

Department of Economics, SMU, Dallas, Texas, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Daniel Slottje

Department of Economics

SMU, Dallas, Texas, USA

Tel: 12143971703

E-mail: dan.slottje@fticonsulting.com

Received Date: December 4, 2015 Accepted Date: December 6, 2015 Published Date: December 16, 2015

Copyright: © 2016 Slottje S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

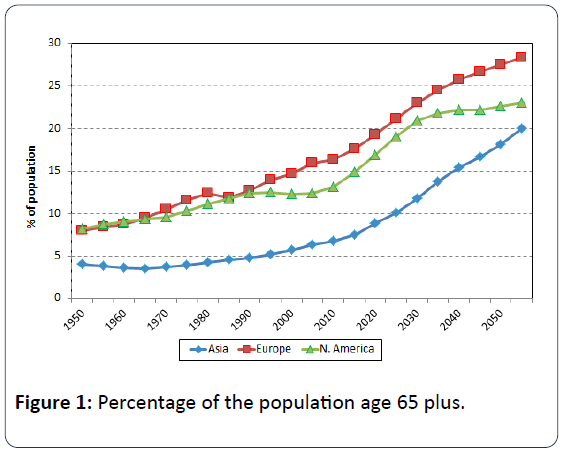

The purpose of this note is to explore some recent significant trends concerning the ageing of the global population and to discuss some of the economic implications therein; and to proffer some ideas on where fruitful research might be conducted by the health economist given these trends. Populations in many countries are ageing. Many countries are experiencing a shift in the distribution of their population towards older ages, caused by rising life expectancy, declining birth rates, or a combination of both. Population ageing is occurring most rapidly in the countries of Europe and North America. Between 1950 and 2015, the percentage of the populations that are age 65 or older has grown from 8% to 18% in Europe, and from 8% to 15% in North America (Figure 1). The United Nations forecasts populations’ continued shift towards older ages through 2055 (Figure 1).

The discussion to follow focuses on the United States, but as seen above, the same economic implications pertain globally [1]. An ageing population in the United States strains public sector resources. In June 2015, the Congressional Budget Office (“CBO”) forecast a long-term fundingshortfall for Social Security of 4.4% of taxable payroll [2]. The projected funding shortfall for Social Security has more than quadrupled estimates made in 2008 [3]. Without an increase in the payroll tax, a reduction in benefits, or a combination of both, the CBO projects Social Security will become insolvent in 2029 [2]. Social Security actuaries attribute the funding shortfall, in part, to declining birth rates and the increasing life expectancy of retirees in the United States.

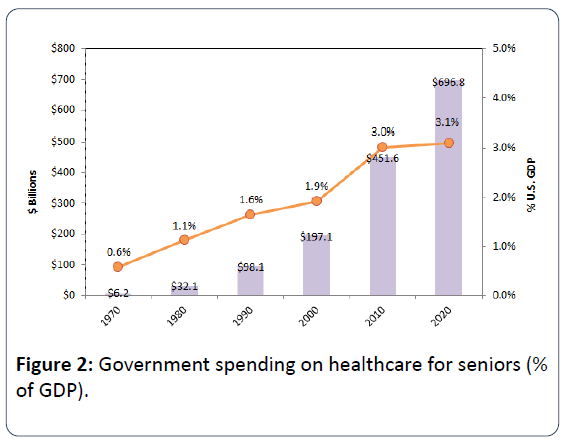

In addition to Social Security, an ageing population in the United States strains public sector expenditures on healthcare. Annual U.S. government spending on healthcare for seniors has increased from $6.2 billion in 1970 to $451.6 billion in 2010, and is projected to grow to nearly $700 billion in 2020 (Figure 2). Growth in government spending on healthcare for seniors has outpaced growth of the U.S. economy over a 50- year time span. Government spending on healthcare for seniors accounted for less than 1% of GDP in 1970, and is projected to account for more than 3% of GDP in 2020 (Figure 2). Growth in spending on healthcare for seniors will likely increase, as the group constitutes a growing percentage of the U.S. population through mid-century.

Geriatrics and End-of-Life Considerations

Coupled with this trend of the graying of the world’s population, one area of potentially fruitful academic research that has not been thoroughly explored is the impact of medicine on end-of-life quality [4]. Specifically, reconsideration of how the medical profession treats the dying could have momentous impact on the healthcare cost crisis currently facing all developed countries. Most people who die in America are elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Care at the end of life is far more expensive for Medicare than spending on a typical beneficiary. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services estimate that more than 25 percent of Medicare spending goes towards the five percent of beneficiaries who die each year. This results in spending on decedents (persons who are in their last year of life) that is six times greater than the cost for a survivor [5].

In a new book, Being Mortal, Dr. Atul Gawande pointed out some remarkable trends. Gawande is a noted surgeon and Harvard Medical School faculty member. First, Dr. Gawande referenced a study from several years ago led by Dr. Chad Boult at the University of Minnesota that shows seniors who receive patient care from geriatricians tend to have higher quality of life, particularly at the end-of-life [6,7]. In randomized trials involving two groups of 568 patients over the age of 70 with similar health profiles in which patients were randomly assigned to either physicians specializing in geriatric medicine (i.e., geriatricians), or primary care physicians, patients assigned to geriatricians had 50% lower depression rates, 25% lower disability rates, and were 40% less likely to require home health services in comparison to patients assigned to primary care physicians [6]. Dr. Boult’s study found that, despite higher quality of life for patients of geriatricians (as evidenced by lower depression, disability, and home health services rates), the mortality rates of patients in both cohorts were the same (10%) [6].

Second, despite these promising findings regarding higher quality of life for seniors who receive patient care from geriatricians, ironically, the University of Minnesota closed its division of geriatrics [8]. When asked why the university elected to close the division of geriatrics, Dr. Boult said: “The University said that it simply could not sustain the financial losses.”[8]. In Boult’s study, the geriatric services cost the hospital $1,350 more per person, on average, than the average savings they produced, and Medicare, the insurer for seniors, does not cover that cost [8]. Closure of the geriatrics division at the University of Minnesota is not an isolated incident. Several medical centers across the United States have downsized or closed their geriatrics units, which has, in turn, depleted the number of healthcare professionals available to deal with the ageing segment of the population. The number of certified geriatricians has decreased by 25% from 1996 to 2010 [9]. Applications in geriatrics and primary adult care have decreased, and incomes of these physicians are among the lowest in the healthcare industry [9]. The trends just discussed and the Boult study raise many interesting questions that is ripe for scrutiny by academicians. Specifically, consider the following:

• The correlation between geriatric medical support and the quality of life (and end-of-life) for seniors seems clear. However, the results emanate from only one study. A single study does not demonstrate causation, but other researchers could certainly corroborate (or not) the Boult findings.

• If the findings are found to be robust, interesting questions arise. The empirical evidence is clear that the number of geriatricians is decreasing. Their target population is increasing, what should healthcare professionals and policymakers do?

• Would raising salaries increase the supply of geriatricians?

• Is it too late to reverse the decrease in supply of geriatricians?

• Could hedonic willingness to pay models come to bear in determining how much to spend on end-of-life healthcare?

• Could such analyses help solve the escalating healthcare cost crisis?

• With most healthcare cost expenditure coming at the endof- life, could changing how the elderly are treated (both while “living” and “dying”) change the very foundation of how healthcare costs rise?

We believe of all of these are interesting questions, and all deserve significant scrutiny by healthcare economists.

References

- United Nations (2015) Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects,The 2015 Revision.

- Congress of the United States (2015) Congressional Budget Office. The 2015 Long-Term Budget OutlookPp:53-55.

- Biggs A (2015) CBO: Social Security Shortfall Quadrupled Since 2008. Fortune.

- https://www.usgovernmentspending.com.

- Adamopolous H (2013) The Cost and Quality Conundrum of American End-of-Life Care. The Medicare News Group.

- Gawande A (2014) Being Mortal.New York:Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and CompanyP: 44.

- Boult C (2001) A Randomized Clinical Trial of Outpatient Geriatric Evaluation and Management. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 4: 351-359.

- Atul G (2014)Being Mortal.New York,Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt & Company Pp:36,45.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences