Medicare Oncology Care Bundle Variation in Cost and Use

Stephen T Parente and Lisa Tomai

DOI10.36648/2471-9927.5.1.42

Stephen T Parente* and Lisa Tomai

Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, 321 19th Avenue South, Room 3-279, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Stephen T. Parente

Carlson School of Management

University of Minnesota, 321 19th Avenue South,

Room 3-279, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Tel: 612-624-2500

E-mail: Stephen.parente@gmail.com

Received date: April 18, 2019; Accepted date: May 06, 2019; Published date: May 13, 2019

Citation: Parente ST, Tomai L (2019) Medicare Oncology Care Bundle Variation in Cost and Use. J Health Med Econ Vol.5 No.1:1

Abstract

Background: Care bundling is an emerging health financing innovation to change the incentives of care, intended to improve quality of care and promote better resource use. In 2016, Medicare outlined a proposal for changing Medicare reimbursement for outpatient drugs through pre-determined care bundles. To gauge the potential for care bundling, we examine one of the first comprehensive efforts, the Oncology Care Model (OCM). This paper shows that the oncology care bundles likely used by OCM have large variation in cost per patient across the United States. Methods: For this analysis, we utilized five years (2010-2014) of the Medicare 5% limited data set (LDS) of fee for service claims. All seven claims segments were used in the analysis including: physician/carrier Part B, durable medical equipment,outpatient hospital, inpatient, skilled nursing facility, home health, and hospice. The 5% LDS sample of Medicare beneficiaries used to identify patients with cancer bundles totaled 17,143 in 2014. An approximate national estimate would be 20 times 17,143, yielding 342,860 beneficiaries. Results: Our analysis of Medicare claims for the three most expensive bundles (lung cancer, prostate cancer and lymphoma) from 2010 to 2014 shows over a 400% difference in per capita bundle reimbursement between US states. Furthermore, we found that the mix of reimbursements within all bundles of fee for service claim types varies meaningfully. Finally, we show that the rank order of most expensive cancers to treat at a patient level is not correlated with the most expensive cancers at a societal level. Conclusions: There is substantial geographic variation in per capita cancer costs that is not consistent for the top 3 cancer bundles. Therefore, policy-making based on system-wide geography will likely not produce a consistent solution. As a result, policy formulation will be challenging when patient cost management is a goal, especially in a healthcare sector where innovation is likely to move faster than robust and thoughtful cost containment strategies.

Keywords

Medicare; Oncology; Cancer diagnosis; Reimbursement

Introduction

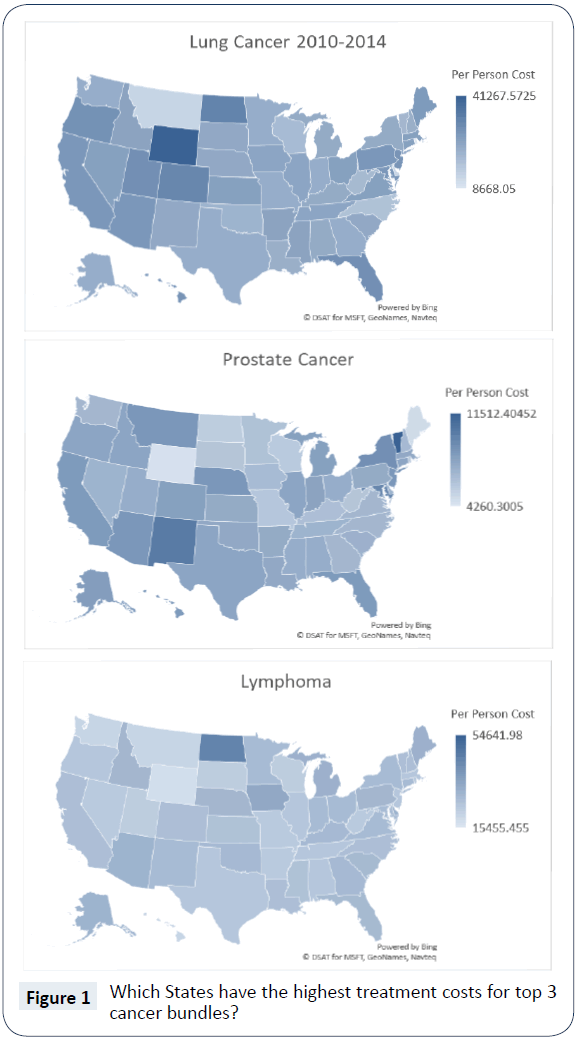

Care bundling is an emerging health financing innovation to change the incentives of care, intended to improve quality of care and promote better resource use. In 2016, Medicare outlined a proposal for changing Medicare reimbursement for outpatient drugs through pre-determined care bundles. To gauge the potential for care bundling, we examine one of the first comprehensive efforts, the Oncology Care Model (OCM). This paper shows that oncology care bundles likely used by the OCM have large variation in cost per patient across the United States. As shown in Figure 1, our analysis of Medicare claims for the three most expensive bundles (lung cancer, prostate cancer and lymphoma) from 2010 to 2014 show over a 400% difference in per capita bundle reimbursement between US states. Furthermore, we found the mix of reimbursements within all bundles of fee for service claim types varies meaningfully.

While the OCM certainly fits the spirit and intent of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) drive for care system innovation through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) [1], concerns regarding the program have been stated. Blasé, Polite and Harold Miller of the University of Chicago criticized OCM, claiming that the $160 beneficiary-per-month payments are insufficient to generate adequate return on savings. Furthermore, they feel the 6-month bundle window could create perverse incentives, leading to worse care for the patient [2]. Of greatest concern is the incentive for an oncologist to delay a portion of a patient's treatment in the first 6-month episode to create a second 6-month episode with additional monthly payments.

This study examines the Medicare fee for service reimbursements associated with proposed Part B oncology drug bundles to highlight major patient-level cost differences prior to the implementation of the new payment method.

Background on Medicare Oncology Bundles

In the United States, more than 1.6 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year, with many of those diagnosed covered by Medicare [3]. To address the prevalence of cancer and the challenges it presents within the Medicare program, CMS proposed the OCM as a multi-payer model focused on providing higher quality, more coordinated oncology care. According to CMS, physician practices under the OCM will enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care surrounding chemotherapy administration to cancer patients. OCM is a five-year model beginning on July 1, 2016 and concluding on June 30, 2021. The authority for the program is Section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) [4]. Over the five-year period [5], OCM costs are estimated at $6 billion for the cancer care of 155,000 patients, with estimated savings of $24.7 billion [6].

The OCM engages multiple payers and care systems. Participating physicians and hospitals can earn $160 per patient, per month, for each month in a 6-month bundle, beginning at the initiation of chemotherapy treatment [7]. To track quality, practices must use an Electronic Health Record (EHR) approved by the HHS Office of the National Coordinator [8]. They must also coordinate care through a care management plan outlined by the Institute of Medicine [9]. To receive payments, practices must show a lower spending per treatment episode when compared to benchmark standards [10]. This benchmark will compare expenditures to "a historical baseline period trended forward to the current performance period" [11]. Analysis similar to what’s presented here may be performed to create the baseline.

Study Data and Methods

Study sample

For this analysis, we utilized five years (2010-2014) of the Medicare 5% limited data set (LDS) of fee for service claims. All seven claims segments were used in the analysis including: physician/carrier Part B, durable medical equipment, outpatient hospital, inpatient, skilled nursing facility, home health, and hospice. The 5% LDS sample of Medicare beneficiaries used to identify patients with cancer bundles totaled 17,143 in 2014. An approximate national estimate would be 20 times 17,143, yielding 342,860 beneficiaries. The population peaked in 2011, at 20,576, with reductions in later years potentially attributable to more Medicare beneficiaries opting for Medicare Advantage plans.

Oncology bundle creation

We developed Oncology Part B Bundles (ONCB) based on cancers identified by CMS for policy development. To create these from Medicare fee for service claims data, we executed six steps. First, we identified only Medicare seniors with both Part A and Part B coverage for the entire year and with no experience in the Medicare Advantage program during the calendar year examined. Second, we identified the start of the care bundle in the 1st half of a calendar year, requiring a beneficiary to have a qualifying cancer diagnosis and health care procedure code (HCPC) indicating the start of cancer treatment. Third, we built a six-month episode of care window per patient, summarizing claims reimbursed for all claims segments and constructing utilization measures including inpatient days and emergency room visits. Fourth, for patients with multiple cancers, we utilized the cancer type tie-breaking logic outlined by the Research Triangle Institute’s approach in the funded CMS contract. Fifth, we created a patient-year specific summary of utilization and cost by ONCB. We also included patient geography identifiers for state-specific analysis and flags to identify beneficiaries who died during the ONCB. Finally, we applied the same logic across five years of data to from 2010 to 2014.

Findings

To examine the most expensive cancer bundles, we focused on the top 3 in terms of total Medicare fee for service expenditures cumulatively, from 2010 to 2014.

In Figure 1, we present the geographic variation in the per capita cost for these cancer bundles: lung cancer, prostate cancer and lymphoma. One clear observation, as we compare the threebundle specific national maps, is there is no consistent pattern in terms of the highest or lowest expense across all three cancers [12]. For example, Wyoming is the state with the highest expenditures for lung cancer, but Wyoming’s costs for prostate cancer and lymphoma are among the lowest. Additionally, we observed a wide gap between highest and lowest expenditures per person with high/low ratios of 4.8 for lung cancer, 2.7 for prostate cancer and 3.5 for lymphoma. Past research suggests there can be significant variation in treatment rates and adherence to treatment guidelines by tumor type across regions within a state, and this could lead to differences in expenditures for various cancers [13].

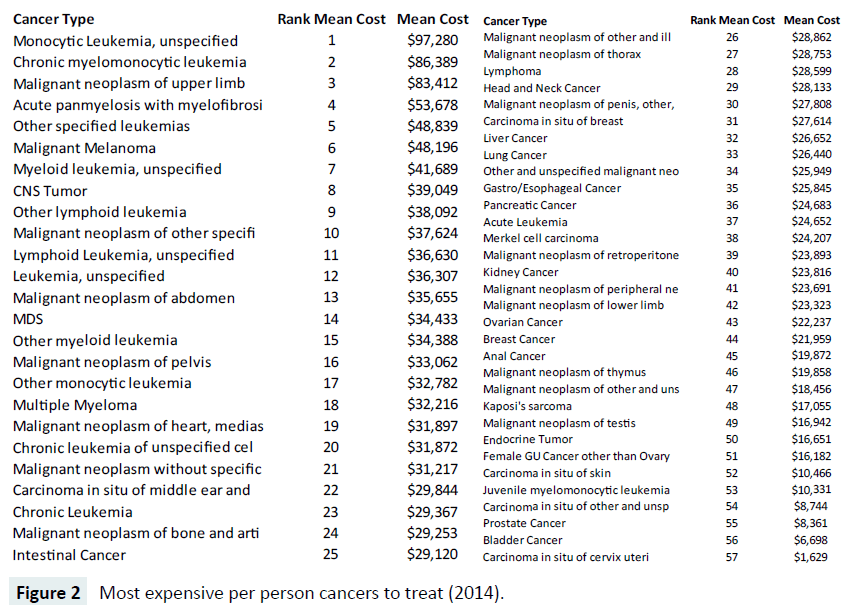

In Figure 2, we display a ranked list of the most expensive cancers at the per capita level in 2014, showing the most expensive cancer is Monocytic Leukemia with an unspecified site, averaging $97,820 nationally. The most expensive cancer (Figure 1), lung cancer, is ranked 37 out of the 57 oncology bundles we examined, with an average total reimbursement of $26,440. Prostate cancer, number two in expenditures nationally, ranked near the bottom of the list at number 55, with $8,361 per capita expenditures.

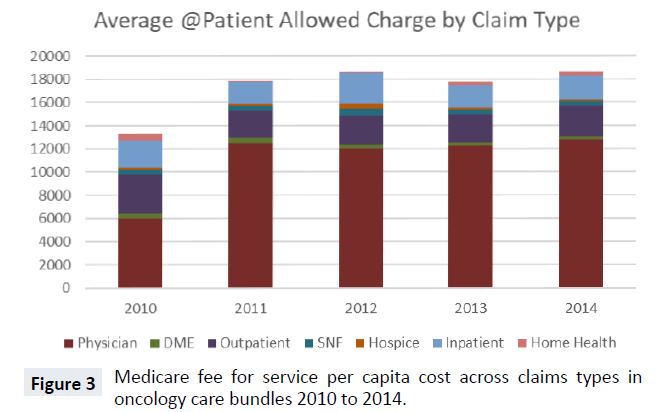

Total cost for the oncology bundles includes seven different claim type reimbursements. In Figure 3, we display the five-year average cost trend for the bundles with stacked claim types. From 2010 to 2011, the total average cost of bundles increased significantly, from just over $13,000 to nearly $18,000. From 2011 on, there was no year-over-year change larger than $1,000. In every year, the largest share of expenditures was physician Part B costs. Outpatient hospital and inpatient (Part A) were the next largest expenditure categories of oncology bundles. Part B drug expenditures are paid under either the physician or outpatient hospital claim types. The remaining four claim types, DME, home health, SNF and hospice, constitute a very small share of oncology bundle costs across all 5 years.

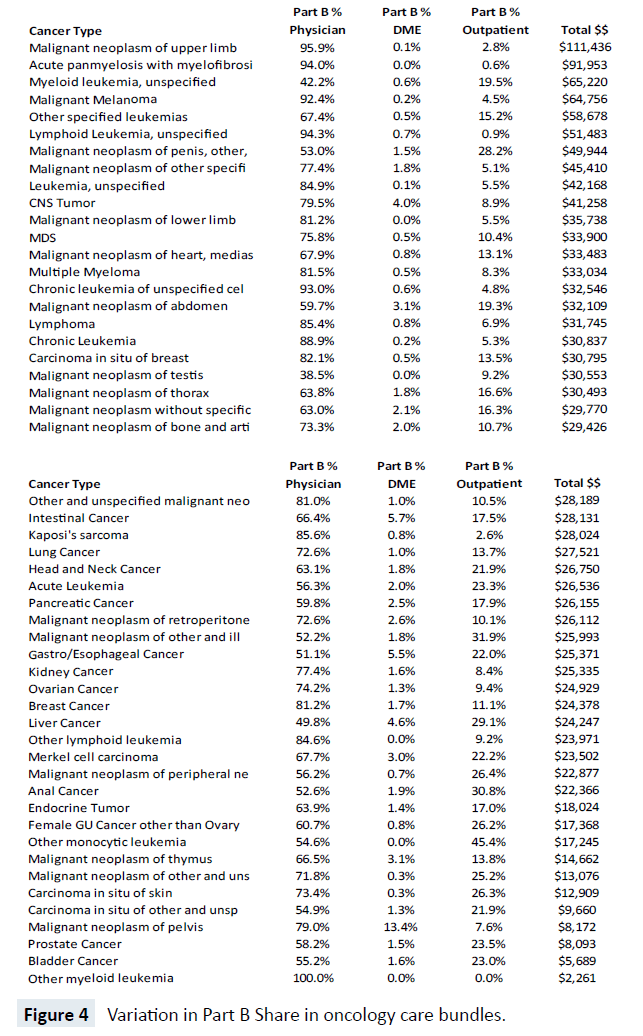

While Figure 3 suggests stable shares of claim types across five years, there is considerable heterogeneity between the cost share for each of the 57 bundles, as shown in Figure 4. For example, the top three most costly cancers at the Medicare program level carry large share differences in Part B physician expenditures. Lung cancer, prostate cancer and lymphoma have Part B physician bundle cost shares of 72.6%, 58.2% and 85.4% respectively and, overall, there are substantial differences in the share of Part B physician expense, ranging from 100% (Other Myeloid Leukemia) to 38% (Malignant Neoplasm of the Testis). Likewise, there are major cost share differences in Part B Outpatient hospital expenditures. The largest share of Part B Outpatient cost is for Other Monocytic Leukemia at 45.4% and the smallest non-zero shares are for Acute Panmyelosis with Myelofibrosis and Lymphoid Leukemia-unspecified, with less than 1%.

Discussion

While cancer is a very health resource-intense illness, we found little inpatient spend in episodes. This made our work challenging when looking at quality of care metrics such as re-admissions. We observed very few deaths in an inpatient setting as well, which would make sense, given that many cancers are not massive acute care events and end of life may be facilitated at an alternative site such as a hospice. Interestingly, we did not find substantial cost in hospice programs within the care bundles. Likewise, relative expenditures for DME and home health were low. Overwhelmingly, physician Part B data was the greatest cost component of oncology bundles.

This analysis has several limitations. First, we cannot draw conclusions about drug efficacy because we didn’t measure it. Second, we are unable to comment on what is the appropriate combination of Part B services, ranging from MRIs, to OBGYN visits to radiation and chemotherapy, inside a bundle that would reduce variation as well as make care more efficient or effective. Despite these concerns, this work provides a starting point for additional analysis looking at cancer staging and subsequent engagement of a clinical advisory committee to look at potentially omitted clinical variables.

From the baseline statistics presented here, policy makers can gauge if success is due to better care or whether it is merely a reflection of improperly set benchmarks due to significant omitted variables in the payment model. Further clinical review is needed to determine the viability of the methodology, and whether real savings will result.

Conclusion

In summary, there is substantial geographic variation in per capita cancer costs that is not consistent for the top 3 cancer bundles. Thus, prioritizing based on system-wide geography will likely not produce a consistent solution. As a result, policy formulation will be challenging when patient cost management is a goal, especially in a healthcare sector where innovation is likely to move faster than robust and thoughtful cost containment strategies. Tackling reduction and management of oncology cost bundles will be a challenge and warrants additional analysis as the OCM policy progresses. One expansion of this study would be to broaden the analysis to include Medicare Advantage claims data from all payer national claims databases that are also Medicare national Qualified Entities (such as the Health Care Cost Institute of Fair Health) to see if the same patterns of care are observable in both the fee for service and Medicare managed care populations. This expanded policy analysis will be valuable if entitlement reform becomes a policy priority for a future Congress.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Non-applicable. No patient medical records were used.

Consent to publish

Non-applicable. No patient medical records were used.

Availability of data and materials

The data used are publicly available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Competing interests

None of the authors have competing interests with the data presented in this analysis.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Pfizer Corporation (US).

Author's contributions

Parente (initial draft, statistical programming, editing); Tomai (statistical programming, algorithm creation and translation, editing).

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the valuable context suggestions made by Deborah Kaye Williams and Bryana Mayer.

References

- Guterman S, Davis K, Stremikis K, Drake H (2010) Innovation in Medicare and Medicaid will be central to Health reform’s success. Health Affairs 29: 1188-1193.

- Polite BN, Miller HD (2015) Medicare Innovation Centre Oncology Care Model: A Toe in the Water When a Plunge Is Needed. J Oncol Practice 11: 117-119.

- https://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/index.

- https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care/

- https://www.politico.com/tipsheets/politico-pulse/2016/06/shooting-for-moon-white-house-holds-cancer-summit-215085

- OCM Performance-based Payment Methodology (2016) Centre for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation.

- Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, Schumacher H, Rajkumar R, et al. (2015) Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Using an Episode-Based Payment Model to Improve Oncology Care. J Oncol Pract 11: 114-116.

- Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Care Services (2013) Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. National Academies Press.

- Clough JD, Kamal AH (2015) Oncology Care Model: Short- and Long-Term Considerations in the Context of Broader Payment Reform. J Oncol Pract 11: 319-321.

- Kline RM, Adelson K, Kirshner JJ, Strawbridge LM, Devita M, et al. (2018) The Oncology Care Model: Perspectives From the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Participating Oncology Practices in Academia and the Community 37: 460-466.

- Vivian H, Ku-Goto MH, Zhao H, Hoffman KE, Smith BD, et al. (2016) Regional differences in recommended cancer treatment for the elderly. BMC Health Services Research.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences