Group Dynamics in Organisations: A Core Literacy for Innovation Leaders in the NHS

Clare Penlington and Patrick Marshall

Clare Penlington1* and Patrick Marshall2

1School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University London, UK

2Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, England

- *Corresponding Author:

- Clare Penlington

School of Medicine and Dentistry

Queen Mary University London, UK

Tel: +44 20 78825555

E-mail: c.penlington@qmul.ac.uk

Received Date: November 02, 2015 Accepted Date: November 19, 2015 Published Date: November 29, 2015

Copyright: © 2016 Penlington C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Purpose:

Individuals attempting to lead change in the NHS are often thwarted in their efforts by complex and powerful group dynamics, many of which operate seemingly unpredictably, actively resisting any alteration to the status quo. If clinicians are to succeed as innovation leaders, therefore, they need a basic literacy with which to navigate these powerful group dynamics. Developing this literacy of group dynamics is a basic building block for all clinical leaders, and without it they are set up to fail as change agents.

Design/methodology/approach:

We outline two theories of latent group processes that we have used to help over 120 junior doctors, participating in a postgraduate module, to understand and navigate service change successfully: Bion’s theory of group mentality and analysis of organisational role.

Findings:

Developing a basic literacy of group dynamics enables clinicians to engage constructively with other healthcare workers and thereby to undertake service improvement projects with more confidence and uccess.

Originality/Value:

The value in this work is that it shows that if leadership programmes are to be successful, they need to prepare doctors to understand their role as change agents within an organisation, and how to work effectively with both the surface and latent dynamics of groups to bring about change. This model of leadership development challenges the current dominant model in the UK which emphasises preparation of individuals, without equivalent attention to the leaders as members of groups.

Keywords

Clinical leadership; Change agency; Service improvement; NHS, Group dynamics

Introduction

In the many leadership programmes that now abound for clinicians, the focus tends to be on developing the individual to innovate and improve services [1-6]. The invisible group processes that this individual leader needs to understand and navigate in order to successfully steer these changes remain, however, in the shadows. In this paper, we present what might initially seem to some as a radical argument. We posit that rather than focusing so much energy on leadership development for clinicians, a more effective approach is to concentrate energies on developing their capacity to analyse and engage with organisations as experiential and relational systems [7]. This involves helping clinicians to develop a literacy of organisations that goes beyond surface structure and processes seen in organisational charts and corporate mission statements. It means preparing workers to notice and attend to the “nonrational, emotional, embodied and unconscious (unaware, taken for granted) side of individuals, groups and organisations” [7] and to therefore equip them with a deeper model of change and development that they can apply to themselves as individuals, and the groups that comprise their organisation.

The rest of the paper is devoted to developing this idea, and showing the benefits of such an approach for a cadre of trainee doctors, based on our experience of designing and teaching a short post-graduate module around these principles. Because our experience has been mainly in working with junior doctors, we draw on examples based on this work here. However, the points we make in this paper are also relevant for other clinical groups, a point we enlarge upon in the conclusion to this paper.

Group processes

Groups are not simply clusters of people, working together towards a single end. Instead, they are complex entities with their own histories as well as emotional dynamics that ebb and flow, at times predictably, but often in ways that seem profoundly unpredictable, and even irrational. In the last few decades there has been an increasing awareness in clinical education of socio-cultural learning theories [8], and how being part of a group has a strong effect on personal and professional identity development.

In our experience of working with trainee doctors, however, an area of scant understanding is how the unconscious life of groups’ influences learning. And, specifically, the way in which groups tend to instinctively collude to avoid learning, because of the threat this change represents to the status quo [9]. Our focus in working with trainee doctors, therefore, had been to help them develop a deeper understanding of group process, and in so doing help them begin to develop a personal guide to the way that unconscious, group processes can have such a profound effect on their clinical work as doctors and as members of their NHS organisations.

There are many theories one could draw upon, in order to help clinicians to begin to develop this personal guide to group processes [10-13] and there are numerous postgraduate programmes which could last for years, focusing on this very issue alone. The theory that we have found to be very useful, as a way of presenting a basic literacy of unconscious group processes is Bion’s theory of group mentality [1,2].

In summary, Bion noticed that every group has a task that they consciously strive to fulfill. This level of group activity Bion labeled the ‘work group’. For instance, on a hospital ward, the clinical team has the task of treating and caring for the patients on that ward and when they are engaged in this task, they are in work group mode. In this mode, a group will be able to observe itself and reflect on what is going on. However, there is another layer of group mental activity, which occurs unconsciously, rather like “powerful emotional drives”[1], and that thwarts the work-group mentality. These basic assumptions seem to operate because, although the group may consciously strive to achieve their tasks, unconsciously they also resist this process, since it represents ‘learning from experience’ which means change to the existing internal order. For example, we might all recognise a situation where we have been part of a group, set with a task that all members agree upon, but which makes little or no progress in achieving it. Bion’s theory is that basic assumptions operate inside all individuals, all the time, but that they become so much more evident when we are in groups. In Bion’s words: “the apparent difference between group psychology and individual psychology is an illusion produced by the fact that the group brings into prominence phenomena that appear alien to an observer unaccustomed to using the group”[1].

In the basic assumption mode, the group acts as one organism. It is as if the individual and an external reality outside the group do not exist; all that exists is the group, and its processes. Attending to the task of the group is subsumed and forgotten-maintaining the group, and all of its processes (and thereby resisting any change) become the group’s primary focus. Bion identified three different basic assumptions: dependency, pairing, and fight-flight.

Dependency

When this basic assumption is in ascendance, the group becomes fixated on the actions of one member-the designated leader. The expectation is that this leader will meet all of the group’s needs, thereby relieving the rest of the group of any responsibility to think things through, or work things out. When this dependency mentality dominates, the designated group leader might feel energised, but simultaneously frustrated at the sluggishness of his or her fellow group members. An example might be when a clinical team meets for the purpose of discussing a potential change in how a fracture clinic is run. One nurse in the group is surprised to find that she begins to talk more and more, whilst the rest of the team sit back, curiously without ideas, focus, or motivation to ‘do the work’ regarding the proposed change. Alternatively, the nominated leader in a group operating in dependency mode might feel overwhelmed and anxious at the pressure to ‘solve things’ for everyone. The designated leader is right to feel apprehensive, because in the dependency mode, her failure to comply with the unspoken demands to ‘do all’ for the group results her immediate overthrow and replacement.

Fight/Flight

In some regards, the flight/flight mode is the mirror image of the dependency mode described above. Instead of the group designating one leader as ‘ultimate provider’ to the group, in flight/flight mode, the group selects an enemy-either within or outside the group-to flee from, or fight, as a way of fostering a sense of cohesiveness within the group. If the clinical team meeting described earlier was dominated by fight/flight, the group may find themselves talking with mounting excitement about the ignorance and foolishness of the management team in the hospital, whose mandates have made it necessary make changes to the organisation of the fracture clinic. The group thereby ‘discovers’ that all members are all in agreement-they feel irritated and angry about how this change is being foisted upon them by ‘management’ and the meeting focuses on how the group will resist this change from ‘on high’.

Pairing

In pairing mode, the focus of the group becomes fixated on two members, who find themselves carrying the hope for the group that they will together produce a ‘leading idea’, which will be the key that ‘unlocks the problem’ and ‘saves the group’. In pairing mode, the two people who are joined find themselves engaging with one another, agreeing or arguing, while the rest of the group become silent and hopeful spectators. In our example of the clinical team, meeting to discuss re-organisation of the fracture clinic, an example of pairing would be a lively discussion occurring between a nurse and a doctor, about the way bookings need to be changed so to better regulate high-need versus low-need patients. As the two clinicians talk, the group is filled with an air of hopeful expectation that they will provide the solution to the problem.

The power of Bion’s model of group mentality is that these processes can be observed in any group [9]. Groups tend to slip in and out of ‘work-group’ mode, with different basic assumption emerging and being enacted, sometimes within moments. Occasionally, a group itself can split into two, with the basic assumptions being assigned to one sub-group, whilst the other functions as the work-group. The important point is that basic assumptions operate unconsciously, so that the group mentality gets enacted without conscious awareness on the part of group members. Having an awareness of them through a basic schemata such as the one we have summarized here, however, does mean that clinicians can become more reflective about basic assumptions, which makes it more likely that when they are engaged in working in groups and teams, they are more able to understand the deviations, and help to guide the activity back to ‘work group’ mode thus increasing productivity.

What this looks like in practice

It might be argued that busy clinicians would find Bion’s theory irrelevant to their day to day management practice. Our experience of working with students on a postgraduate module on change and leadership, however, showed that they found it resonated with their experience of working within their teams and helped explain why things happened in particular ways. Perhaps even more importantly, an understanding of how teams operate can helped these doctors to ‘notice’ and reflect on their own behaviours when working in groups, which in turn makes them more productive and constructive team members.

We required the doctors on the postgraduate module described above to devise and conduct a service improvement project, over a 4 month period. The assignment for the module comprised a write up of what occurred, including a reflection on how they operated as leaders of the clinical changes they championed. In so doing, clinicians became more aware of how they actually operated inside their own team and departments as well as their role within the complex system of the NHS.

During this module, one trainee doctor focused his improvement project on the impact of near peer teaching organised by junior doctors for final year medical students. In the process of leading this project he encountered the problem of keeping all the other junior doctors fully involved and contributing to the design and implementation of an improved teaching programme. As part of his reflection on the process he drew on Bion’s basic assumptions to help him identify the growing tensions within the working group of junior doctors and to consider how changes in his leadership behaviour contributed to making the group more effective.

The following excerpt shows how he framed this emerging new understanding of the group he was working in and leading. It is important to note that it was through using Bion’s theory of group mentalities as a reflective tool that the trainee doctor was able to gain insight into what had occurred:

“Whilst the colleague and I who set up the group had a constructive relationship we were initially not keen to share responsibility with the others involved in the project. They [other group members] also tended not to ask to take on any more roles but would wait each week for us to tell them what to do and to provide material. This appears to reflect one of the basic assumptions from Bion’s work on groups, namely pairing. There was an intense focus between two of us and passivity from the rest of the group which was not as productive as it could have been. Later in the project when more responsibility was shared with group members from the regional centres the project worked better with a higher quality of material. I certainly learnt that once I began to trust other people to undertake tasks, the standard of the programme improved.”

We would argue that it is this understanding of the otherwise invisible group processes rather than a focus on his individual development as a leader that gave this trainee doctor the conceptual framework to engage in this service improvement project change in a manner that supported both his team and the development of the near-peer teaching programme. Further, because this learning was ‘discovered’ by him we would suggest that there is more chance that it will form part of his personal understanding of how groups work, influencing how he engages with others in the clinical setting, in the future.

Understanding roles in organisations

All organisations have idiosyncratic features, and what they look like from the outside can differ markedly on what they feel like ‘on the inside’ after a person has been working there for some time. Entering an organisation and the ‘new starter’ walks over the threshold with his or her identity and sense of agency intact. Immediately, however, they also enter a system with its own history, culture, and ways of organising the people and resources within it. In other words, as soon as a person steps into a workplace, there begins a complex and intricate dialectic between his or her individual identity and the broader milieu of that group. ‘Shariq the doctor, or ‘Cal the nurse’ starting work at a new hospital or GP surgery do not simply accrue a new professional role, they also inevitably absorb and internalise aspects of this new setting: just as the organisation is changed by their presence, both Shariq and Cal are also irrevocably altered by being there.

In our work with trainee doctors on the postgraduate module described earlier, we found that helping them to understand how role emerges from an intricate interplay between personal dynamics and those of the organisation is an idea they have not had opportunity to contemplate in any great depth. Thus, they greatly appreciated being afforded a chance to consider how, just as we ‘get inside organisations’ when we take on a new job, the converse is also trueorganisations ‘get inside us’ and as such, have a profound influence on our thinking, feeling and imagination of what is possible in that setting. Below we set out the two main ideas that we think are central to explaining this to clinicians: the concept of role as developed by ‘organizational role analysis’ [14] and the theory of ‘organisation in the mind’ [15].

Role

Our common-sense understanding of ‘role’ within organisations tends to focus on titles, our place in the hierarchy, and the sorts of tasks we do on an everyday basis. However, this version of role really only reveals the manifest aspects, leaving the deeper or latent layers hidden from view. One aspect of this latent level of role is the hidden expectations that are placed upon a person by the organisation [16-18]. These are bit like the ‘shadow’ job description, the parts of the role that you might find out about if you were a new starter, and had opportunity to ask the previous post-holder: ‘so, what’s it really like to work here, in this job?’. This unspoken or ‘shadow’ side of the job description is often a lived reality-it certainly does not appear on the HR description of the role, and it generally is not talked about, openly. Rather, this informal/hidden/shadow side of the role becomes part of your knowledge about it, through doing the role, over a period of time.

Organisation-in-the-mind

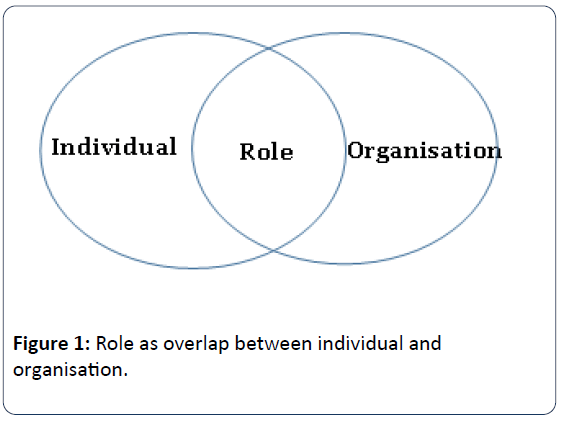

The second aspect of role that clinicians tend not to be aware of, at a conscious level, is the way in which it emerges from a dynamic dialectic between an individual and the organisation as depicted in Figure 1.

One way we have used to get trainee doctors to reflect on this dialectic is to get them to draw a picture (using as many symbols as possible, rather than words) of the NHS organisation they worked within as they currently experience it. Through doing these drawings, the trainee doctors have been able to reflect on the ‘organisation in the mind’ that they hold. ‘Organisation in the mind’ is a kind of mental mapping or image they hold of how the organisation ‘works’. Our experience of getting trainee doctors to reflect on these pictures of their ‘organisation-in-the-mind’, is that we are able to begin to get them to think about how role is shaped from a dynamic between what they bring (their memories, hopes and fears of what organisations can ‘do’) and what the organisation offers them by way of experience and resource. Through looking at this picture of their ‘organisation-in-themind’ it therefore becomes more possible see things about their role that previously remained out of sight, and thus could not be thought about.

Creating these pictures of their own mental maps of the organisations can also prompt clinicians to formulate hypotheses about the differences and similarities in ‘organisation in the mind’ held by other individuals and groups within the institution [3]. For example-considering the similarities and dissimilarities between the mental mapping held by doctors and managers, or clinicians and non-clinical staff. These kinds of reflections help clinicians to contemplate the way that, just as much as a hospital or GP surgery exists of bricks and mortar, workers and patients, team and departments, so too these organisations exist ‘in the mind’, and that these inner mappings have a powerful effect on the day-to day interactions between health care workers, and their contemplations about what is possible and impossible in that setting.

What this looks like in practice

A trainee doctor undertook a project, as a part of the postgraduate module we were teaching, focused on developing a nurse-led jaundice clinic to meet an identified need for service improvement. The planned clinic did not eventuate within the timeframe of the module assignment, but the doctor continued with the project later, and the clinic did eventuate, resulting in a considerable improvement in screening and follow-up of babies with prolonged jaundice seen at the Trust. As teachers of the postgraduate module, we expected that they service improvement projects would not always succeed, and made this clear to students. We wanted projects to do well, of course, but communicated that our primary expectation was not this success, but that the doctors would learn from what they had undertaken. The trainee doctor who had undertaken this project on the nurse-led jaundice clinic, developed a narrative of her learning for her final assignment. As she reflected on some of the practical steps she took in getting the proposal accepted by key players, she used the concept of ‘oragnisation-in the mind’ to make sense of what occurred.

Author began by arranging an appointment with Mr Z, a consultant paediatric surgeon… who gave insightful advice on how to pitch my proposal in a way that was receptive to the different priorities of the individuals involved. This extremely useful session heightened my awareness of the varied territories that comprised the ‘organisation-in-the-mind’ of the different senior power-holders at the Trust.

The doctor returned to draw upon the theory of ‘organisation-in-the-mind in her conclusion, as she reflected on what she had learned. What is particularly interesting about the doctor’s reflections is the connection she makes between overall organisational culture and the ‘organisationin- mind’.

Though there are on-going many surface reforms which are changing HOSPITAL X’s structure as we know it, in many areas there is a desperate need for a re-evaluation of the organisational culture it still perpetuates. Our experiences illustrate how growth and progress within a Trust can be held back by traditional hierarchical command and control leadership styles. Though the outside frame-work may change, if there is no shift in the ‘organisation in the mind’ active within each individual leader, the inherent managerial culture stagnates and its set-backs persist, sabotaging external efforts to enable a healthier work-place environment to flourish.

Conclusion

The current trend in leadership education in the NHS is to enliven and inspire individual clinicians to become innovative and effective leaders-helping to develop the NHS to better meet the hefty challenges it currently faces. The argument we make in this paper, is that whilst this aim is worthy, the means of achieving it must include providing doctors and other clinicians with the tools they need to navigate the invisible, but powerful unconscious terrain of the NHS as an organisation. In the courses we ran for junior doctors which were labelled ‘leadership courses’ we were very clear that our goal was not one of preparing them to be individual heroic leader, but rather to be proactive and effective team players-and to take on the role of leader or follower, as the situation demanded it. In the foreground of this course was our focus on providing doctors with a way of understanding the way their organisation worked, and their own role within it, beyond the surface, through to the powerfully emotional and unconscious group dynamics. The power of this knowledge is that it provides clinicians with a personal guide about how to begin to make change within this complex setting of an NHS organization-and a more realistic notion of the extent to which they can become agents of change. Our experience as educationalists shows that there are strong benefits in equipping clinicians, at all levels (i.e., not just managers and formal leaders), with this basic literacy of the non-rational, unconscious aspects of organisations.

First, it provides clinicians with a “shared interpretation of experience” and thus is a way of developing lateral bonds between clinicians [19]. In the endlessly reconfigured NHS these lateral connections between clinicians become all the more important providing a “shared perspective that transcends the individual, joining him to others and relieving the perplexing sense of being lost amidst the rapidly changing (and rarely interpreted) structures” [19]. These lateral connections also remind clinicians that first and foremost they are a member of a team-a group that has to work together if the NHS is to survive the considerable challenges that it currently faces.

Second, this literacy of the unconscious dimension of the NHS represents an educative process that empowers, not just individual clinicians, but also the teams and departments in which they work. We argue that increasing levels of this kind of organisational literacy has great potential to make positive changes to the culture of NHS organisations, for the benefit of patients and staff alike. This is because gaining an understanding into the ways groups and organisations function, beneath the surface, helps clinicians to have more compassion and understanding for themselves as group members, and for others within the groups and organisation in which they work. Providing clinicians with an opportunity to understand the way their organisations work, and their role in this setting confirms them in their identity as member of an organisation with the result that they are more invested in collaborating with others to improve services.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many junior doctors within KSS Deanery who participated with such vigour and enthusiasm in the postgraduate module ‘Leadership in Clinical Contexts’ between 2011 and 2014. In particular we are grateful to the two doctors who kindly gave their permission for us to use excerpts from their service improvement projects, in this paper. No external funding has been received for this research.

References

- Bion WR (1961) Experiences in groups,Tavistock, London.

- Bion WR (1952) Group dynamics: a review. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 33: 235-247.

- Reed B, Bazalgette J (2006) Organizational role analysis at the Grubb Institute of Behaviourial Studies: Origins and development. Coaching in Depth: The Organizational Role Analysis Approach 43-61.

- Bleakley A (2006) Broadening conceptions of learning in medical education: the message from teamworking. Medical education 40: 150-157.

- Edmonstone JD (2014) Whither the elephant? the continuing development of clinical leadership in the UK National Health Services. The International Journal of health planning and management.

- Caldwell G (2014) Is leadership a useful concept in healthcare? Leadership in Health Services 27: 185-192.

- Diamond MA, Allcorn S (2009) Private selves in public organizations: The psychodynamics of organizational diagnosis and change, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Stokes J (1994) The unconscious at work in groups and teams: contributions from the work of Wilfred Bion. In: Obholzer A, Roberts VZ (eds.) The unconscious at work: Individual and oragnizational stress in the human services, London Routledge.

- Yalom ID (1995) The theory and practice of group psychotherapy, Basic Books, New York.

- Foulkes SH (1983) Introduction to group-analytic psychotherapy: Studies in the social integration of individuals and groups, Karnac Books, London.

- Miller EJ, Gould LJ, Stapley L, Stein M (2004) Experiential learning in organizations: Applications of the Tavistock group relations approach, Karnac Books, Lodnon.

- Mersky RR (2012) Contemporary methodologies to surface and act on unconscious dynamics in organisations: An exploration of design, facilitation capacities, consultant paradigm and ultimate value. Organisational and Social Dynamics: An International Journal of Psychoanalytic, Systemic and Group Relations Perspectives 12: 19-43.

- Newton J, Long S, Sievers B (2006) Coaching in depth: The organizational role analysis approach, Karnac Books, London.

- Armstrong D (2005) Organization in the mind: Psychoanalysis, group relations, and organizational consultancy: Occasional papers 1989-2003. Karnac Books, London.

- Sievers B, Beumer U (2006) Organisational role analysis and consultation. The organisation as inner object. In: Newton J, Long S,Sievers B (eds.) Coaching in Depth: The Organizational Role Analysis Approach. London: Karnac.

- Vince R (2002) Organizing reflection. Management learning 33: 63-78.

- (2014) NHS Leadership Academy, Leeds: NHS Leadership Academy.

- Shapiro ER, Carr AW (1993) Lost in familiar places: Creating new connections between the individual and society. New Haven, Yale University Press.

- Bion WR (1961) Experiences in groups,Tavistock, London.

- Bion WR (1952) Group dynamics: a review. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 33: 235-247.

- Reed B, Bazalgette J (2006) Organizational role analysis at the Grubb Institute of Behaviourial Studies: Origins and development. Coaching in Depth: The Organizational Role Analysis Approach 43-61.

- Bleakley A (2006) Broadening conceptions of learning in medical education: the message from teamworking. Medical education 40: 150-157.

- Edmonstone JD (2014) Whither the elephant? the continuing development of clinical leadership in the UK National Health Services. The International Journal of health planning and management.

- Caldwell G (2014) Is leadership a useful concept in healthcare? Leadership in Health Services 27: 185-192.

- Diamond MA, Allcorn S (2009) Private selves in public organizations: The psychodynamics of organizational diagnosis and change, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Stokes J (1994) The unconscious at work in groups and teams: contributions from the work of Wilfred Bion. In: Obholzer A, Roberts VZ (eds.) The unconscious at work: Individual and oragnizational stress in the human services, London Routledge.

- Yalom ID (1995) The theory and practice of group psychotherapy, Basic Books, New York.

- Foulkes SH (1983) Introduction to group-analytic psychotherapy: Studies in the social integration of individuals and groups, Karnac Books, London.

- Miller EJ, Gould LJ, Stapley L, Stein M (2004) Experiential learning in organizations: Applications of the Tavistock group relations approach, Karnac Books, Lodnon.

- Mersky RR (2012) Contemporary methodologies to surface and act on unconscious dynamics in organisations: An exploration of design, facilitation capacities, consultant paradigm and ultimate value. Organisational and Social Dynamics: An International Journal of Psychoanalytic, Systemic and Group Relations Perspectives 12: 19-43.

- Newton J, Long S, Sievers B (2006) Coaching in depth: The organizational role analysis approach, Karnac Books, London.

- Armstrong D (2005) Organization in the mind: Psychoanalysis, group relations, and organizational consultancy: Occasional papers 1989-2003. Karnac Books, London.

- Sievers B, Beumer U (2006) Organisational role analysis and consultation. The organisation as inner object. In: Newton J, Long S,Sievers B (eds.) Coaching in Depth: The Organizational Role Analysis Approach. London: Karnac.

- Vince R (2002) Organizing reflection. Management learning 33: 63-78.

- (2014) NHS Leadership Academy, Leeds: NHS Leadership Academy.

- Shapiro ER, Carr AW (1993) Lost in familiar places: Creating new connections between the individual and society. New Haven, Yale University Press.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences